Edward Munch: A 19th century feminist or misogynist?

Words by Edie Bell-Brown

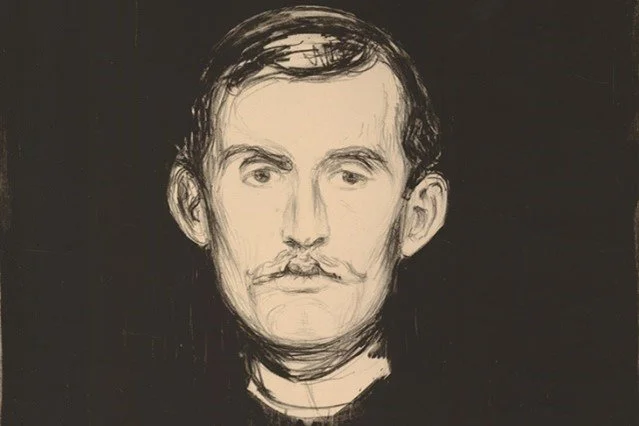

“Self-portrait”, Edvard Munch, c.1895, lithograph.

Edvard (Edward) Munch (1863-1944) is one of the most notable artists of the Symbolist movement during the 19th and 20th centuries who controversially at the time explored themes of love, sickness, death, and loneliness. Renowned for his painting ‘The Scream’, depicting anxiety and suffering of human existence, it is one of the most famous pieces of Western art today. He is certainly seen as a troubled artist as he drew inspiration from his personal life for his work. He experienced death and loss at a young age, losing his mother in 1868, and he had a dysfunctional relationship with his widowed father and siblings. In his adulthood, many of Munch’s troubles were blamed on his relationships with women, which evoked ideas of love, jealousy, sexuality, and procreation within his artwork. Munch’s women within his work are depicted as a symbol of sexuality and fertility, but is this liberating or condemning?

“Madonna”, Edvard Munch, c.1895, lithograph. “Madonna”, Edvard Munch, c.1894, oil painting.

Munch’s ‘Madonna’ (1894-95) is a pivotal example of a woman empowered by her unapologetic sexual desires. ‘Madonna’ has religious connotations, better known as Virgin Mary, Jesus’ mother, and a symbol within Christianity of purity and motherhood, all characteristics which women were expected to have. Munch’s work attaches an entirely new meaning to ‘Madonna’ as he diverges from the traditional depiction of the mother of God and presents a mother of modern society. This contemporary depiction of a religious figure isn’t surprising from Munch, as he was raised by a highly religious and nihilistic father, which pushed Munch away from his own religious devotion to more modern societal values - such as female empowerment. The ‘Madonna’, as seen in the painting, is an embodiment of the femme fatale, as she appears nude, her pale peachy skin contrasted by the deep red halo on her head which symbolises temptation and sexuality. This is an interesting choice by Munch as the halo is the only symbol related to the Virgin Mary within the painting. The strokes of blue, brown, and red colour create a sexual aura surrounding her, juxtaposed by her black hair falling down her body. Her facial expression highlights her arousal and liberation within her sexual desires. Munch’s lithographic version of the painting features a ‘ghoulish foetus’ linking to ideas of motherhood. The foetus in the outer edge of the frame can be seen as representation of the new era of society for women, who now can enjoy sex freely without the expectations of motherhood, with the new widely available choices of contraception and even abortion.

“Vampire”, Edvard Munch, c.1895, oil painting.

In ‘Vampire’, we see the stereotypical roles of men and women reversed, the man is depicted as weak and vulnerable whereas the woman is presented as a femme fatale. The male figure embraces the woman and lies on her lap with his face turned away from the viewer. The brushwork highlights her glowing red hair, possibly a symbol of blood or even poison, contrasting the dark and dull colours within the painting. Her hair falls over him and engulfs him, certainly capturing the attention of the observer. Is she comforting him, gently cradling him, and kissing his neck? Or is she truly a ‘vampire’ sucking the life out of him, as there is a greyish tint to his skin which reinforces this idea that she has consumed him, until he is drained and helpless? Munch has created this genius metaphor to show the power of the ideas of femme fatale, by representing the destructive nature of women and the suffering they cause to men.

Edward Munch lived at a time where first wave feminism was rising, as women emerged from their domestic life and demanded their place in society, focusing on their right to vote. Munch can be argued to have contributed to the movement as both ‘Vampire’ and ‘Madonna’ are examples of celebrated sexually active and powerful women. Qualities which should be seen in society as natural and liberating for women, and not shunned for.

“Woman in Three Stages”, Edvard Munch, 1985, oil painting.

The painting above, Munch’s ‘Woman in Three Stages,’ depicts the cycle of life for women, as they move from one female archetype to another from left to right: the virgin; the lover and mother and the old woman. The young maiden, a symbol of purity in her white dress with light surrounding her, faces towards the sun. The second woman stands provocatively facing the viewer, emphasising her sexuality and womanliness as she is fully nude, stood wide and brazen, somewhere halfway between the light and darkness. The third woman, who can barely be seen, hides within the dark with a deathly perhaps ghost-like expression, is reaching the end of her life with a man on the other side of the tree trunk. Despite it being a painting of the stages of a woman’s life, the man within the painting represents the reality of a woman’s life which is to be perceived and determined by men. Munch’s representation of women is subdued, presenting them as helpless to these three stages of life pre-determined by biological and sexual forces, enforced by society.

Despite Munch’s work surrounding women being progressive for 19th Century societal norms, Munch’s work can be seen in a misogynistic light. His motifs behind his female artwork seem to be narrow-minded rather than empowering, objectifying women as hypersexual. He looks through the ‘male gaze,’ seemingly obsessed with presenting women as sexual objects, even sexualising a young girl in his most disturbing piece ‘Puberty’ (1885). Munch seems to personify his own personal desires, by giving women the roles of only adulterer and procreator, leaving no room for them to be a part of the male-dominated intellectual and professional sphere.