Piero Gilardi and the appeal of artificial nature.

Words by Jacopo Cavini

The artworks displayed in Norman Rea’s current exhibition, “Perceiving Nature”, reflect the complicated relationship between our society and the natural environment. But, as art has always been influenced by nature, it would be wrong to assume that this is just a concept related to our contemporary climatic issues.

The 1960s were a period of great social unrest in western countries: people, and especially artists, were well aware of the rapid modernization of mass production, the introduction of plastics and the shift from agricultural to consumeristic society. The contrast was even starker in countries like Italy, which had witnessed an “economic miracle” that had rapidly transformed it into an affluent and modern country, to the cost of pollution and natural destruction. In this context, a group of young neo-avant-garde artists started reflecting on the relationship between nature, society and art representation. This movement was later called Arte Povera (“poor art”) due to their preference for worthless materials, such as plastic, metal, wires and similar.

Image of Piero Gilardi’s exhibition in Ileana Sonnabend’s gallery in Paris, 1967. Courtesy of the artist via artnet.com.

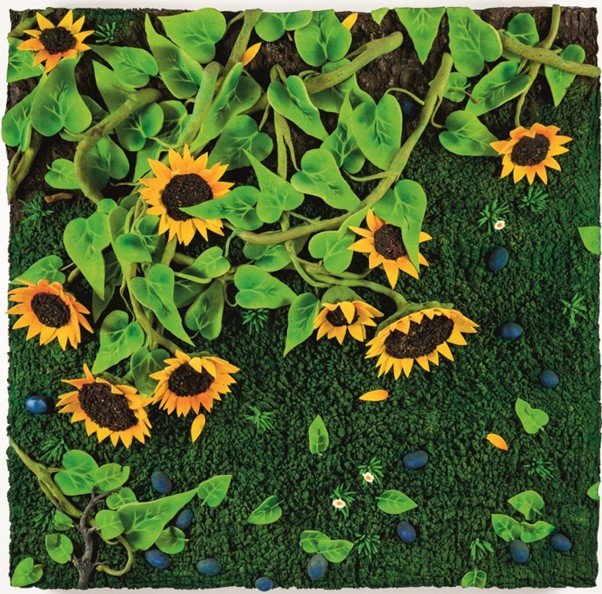

Among these artists, a preeminent figure was Piero Gilardi (1942-2023), the inventor of the Nature-Carpets. The idea behind these “sculptures” is simple: the artist took a coil of polyurethane foam, cut it in a square or rectangle, and then filled it with hand-carved, vibrantly-colored polyurethane foam reproductions of natural elements. This simple yet effective method allowed Gilardi to create dreamy landscapes, small pieces of nature that could be placed in a room and transform it into somewhere else: an orchard with apples fallen on the ground, a stony bed of a dry river, even a sea with waves and flying (fake) seagulls.

Piero Gilardi, Fallen Sunflowers, 1967. Piero Gilardi private collection.

In this video you can see Gilardi’s creative process and the following exhibition of his works.

Piero Gilardi, “Sea”, 1967. Galleria Girardi, Livorno.

Since the first time they were exhibited in 1965, the success of these carpets was immediate with both the public and critics. Gilardi had staged them coiled like real carpets: they looked like artificial nature, that could be reproduced and sold by the meter – that’s why they are often mistaken for mass-produced design objects (as their name suggests), while they are actually hand-made sculptures.

The artist during the set-up of his exhibition at the Fishbach Gallery, New York 1967. Courtesy of Centro Studi Piero Gilardi via flash---art.it.

Gilardi himself encouraged visitors (and purchasers) to have a spontaneous and informal relationship with his creations: they could be displayed under a glass like a precious artifact; exhibited in the middle of the room like a sculpture or hung on the wall like a painting. He wanted people to play with them, even picnic on them if they fancied – apparently, children were very eager to use them creatively.

Courtesy of Centro Studi Piero Gilardi, via flash---art.it.

But how did Gilardi perceive nature? From the environmental point of view, the implications of his artworks are interesting and somehow controversial. Gilardi uses polyurethane foam: an indefinite material that can become anything but is not even remotely natural. The inspiration came from window dressers and stage designers, who needed a material which was resistant and quick to use for their sets.

His representation of nature is extremely artificial: it wants to appear pleasant rather than realistic. The colors are always vibrant and cheerful, even when they try to mimic the stains and imperfections of rocks and rotten fruits. There is also the evident softness of plastic foam, that makes people want to play or lay on his sculptures. In conclusion, a fake material for a fake world.

A theme that he seemed to suggest with his work is a sort of infinite reproducibility of nature. His landscapes were presented as coiled up and then unrolled, just like in a fabric showroom. Nature looked like something that could be reproduced, customized, and bought to decorate your own living room.

As already claimed in the 1960s by critic Ettore Sottsass, this is fine, because modern humans live in such a modified world that this fake reality is enough for them. In his famous comparison, a Nature-Carpet is a realistic sublimation of a landscape, fit for a society that uses Ketchup as a realistic sublimation of tomato sauce. The same label that is often used to promote modern products, “for reasons of hygiene and comfort”, clearly denies their authenticity, and the same time makes them more desirable for our modern needs and wishes.

Perceiving nature as decoration has been a constant in human life, but in our contemporary society, where the digital world has become a more appealing duplicate of the real one, the risk is that nature might be considered just as a nice interior decoration, when it is actually about the entire ecosystem of which we are part, with its’ endangered species, impoverished soils, and rising temperatures. In this sense, Gilardi’s artworks remind us that the risk of fetishizing the idea of a beautiful nature indoors is forgetting the real, endangered nature outdoors.

The exhibition in Magazzino Italian Art, Cold Springs (NY), 2022. Via flash---art.it.