Remedios Varo, on Love: A Remedy for Logic

Words by Madeleine McClean

it is most mad and moonly

and less it shall unbe

than all the sea which only

is deeper than the sea

from ‘[love is more thicker than forget]’

e.e cummings then goes on to state that Love can also be ‘most sane and sunly’; it is a mercurial thing. Love is something that artists and poets alike have sought to capture and express since the start of art and poetry, and it is often described as a kind of madness, illogical and passionate. Or else serene and quietly healing, but still within its own elusive system. The Norman Rea Gallery exhibition ,‘The Practice of Love’ (opening Wed 19th March, 6:30, in the Gallery!), promises to showcase a variety of approaches to the subject, from the moonly to the sunly. And though the term ‘Practice’ evokes discipline and arithmetic, I have chosen to take a look at the work of a woman whose art, though disciplined in its execution, nonetheless works to transcend the rational and enter the world of the surreal. Remedios Varo, once a member of the art collective the Logicofobista, did indeed produce art that seems phobic of logic, which may be only to say that they can better approach the illogic of love.

‘Los Amantes’, 1963

Varo’s oeuvre is defined by its interest in the metaphysical, the alchemical and the mystical, which are expressed in her dreamlike landscapes and surreal subjects. As Octavio Paz puts it, hers is ‘the art of levitation: the loss of gravity, the loss of seriousness. Remedios laughs, but her laughter echoes in another world’. Love was really of secondary importance to Varo; she reportedly saw the many love affairs of her life as a distraction from and an impediment to her art, rather than a fuel for it. This perspective is perhaps important to bear in mind when observing her most explicit allusion to love in ‘Los Amantes’. Two lovers, as we are told by the title, sit with fingers interwoven and eyes interlocked. This electrifying union generates steam which turns into rain clouds, which in turn pour into the flood at their feet. Are these cleansing waters or do they threaten to sweep the lovers out to sea if allowed to rise? The colour palette is sombre and brooding, like the look they share. As Varo believed in ‘love as a higher expression, where freedom and development of the self is part of a true relationship’, the mirrors could represent the fusion of two souls into one, as each partner absorbs and reflects the desires of the other. Alternatively, the mirrors represent a narcissist attraction within a love that is ultimately shallow and futile, doomed only to distract Remedios from her art. The bench provides the only point of stability, though even its foundations are compromised. Everything is in flux, changing states and defying concrete logic. Within its narrow composition it conjures the possibility of transcendent expansion, conveying an altogether ambivalent approach to amore.

‘The Garden of Love’, 1951

Painted over a decade earlier, this painting retains a dreamlike quality, though the forms seem sharper and the colours brighter. Straddling the earthly and ethereal realms, we witness what appears to be a tryst between the apparition of a lady and a vibrant crow, donning the robes of a dashing 18th century nobleman. She is framed by the strict manmade shapes of a classical façade, whereas he is at ease amidst the organic forms of the trees and the birds, painted so garishly so as to draw attention to their importance to the overall allegory as symbols of freedom. An allegory rooted in artistic tradition, reaching back to Classical and Renaissance tropes in which the ‘Garden of Love’ was a luscious space symbolic of fertility and pleasure, once described by Sufi mystic poet Rumi as:

The garden of love is green without limit

and yields many fruits other than sorrow or joy.

Love is beyond either condition:

without spring, without autumn, it is always fresh.

— Rumi, Masnavi I

The ideas expressed by Remedios’ work seem to me to be more acutely expressed in William Blake’s poem of the same title, as there is a tension between ‘The Chapel’ (representative of the manmade and dogmatically prescribed Loves, which are aligned with death), and ‘The Garden’ (representative of natural freedoms - these are aligned with life, like the flourishing forest on the right side of the painting). Like Blake, Varo is interested in mysticism and mystical union, and considered Surrealism as ‘an expressive resting place within the limits of Cubism, and as a way of communicating the incommunicable’. This painting is then her idea of communicating the almost incommunicable logic of love, which for her encompasses a seemingly spiritual experience that can only be alluded to through complex allegory.

The Garden of Love

By William Blake

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And 'Thou shalt not' writ over the door;

So I turn'd to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

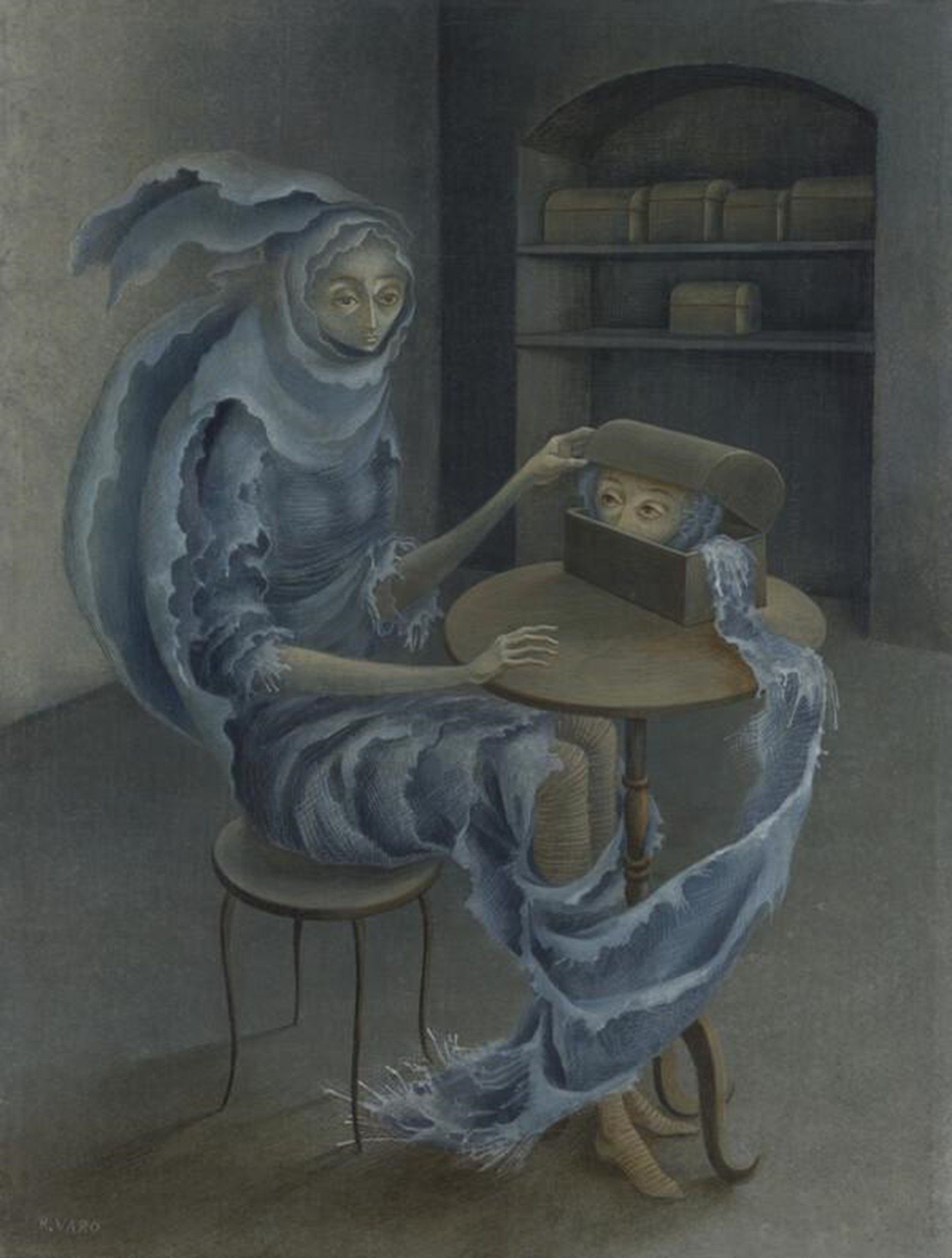

‘Encounter’, 1959

However, it could be said that Remedios’ oeuvre is predominantly interested in encounters with her self, rather than entanglements with others. Highly influenced by psychoanalysts such as Carl Jung, she was invested in her own subconscious. In this painting, she opens a box only to see her own eyes staring back at her; there are many more boxes on the shelf, suggesting a series of selves she has yet to uncover. As water often symbolises the unconscious, the fluid drapery further suggests that this is a representation of the mind.

When it comes to love, Varo provides an otherworldly visual language that can help us grasp its ineffable qualities. However, her sense that it could be a distracting rather than edifying affair is echoed in her work, and the mirrors of ‘Los Amantes’ could just be another reminder that one of the most profound ‘Encounters’ we should pursue is with ourselves; to repeat Kaplan’s assertion, for Remedios ‘the knowledge of the other will reflect upon the knowledge of the inner self’ and ‘development of the self is part of a true relationship’.

‘The Star Catcher’, 1956

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Octavio Paz, ‘Remedios Varo’s Appearances and Disappearances’, 1966

J. Kaplan, Unexpected Journeys: The Art and Life of Remedios Varo, Abbeville Press, New York, 1988, p. 130, n. 131 (illustrated in color) R. Ovalle, W. Gruen, A. Blanco, T. del Conde, S. Grimberg, J. A. Kaplan, Remedios Varo-Catálogo Razonado, Ediciones Era, Mexico City, 1994, p. 228, n. 356 (illustrated in color)