‘Women’s Work’ as Protest: The History of Feminist Protest Quilts

Words by Evie Brett

Throughout history, feminist groups have employed quilted banners as a primary signifier of protest. Making use of textiles, needle-craft and embroidery, all tenets of so-called ‘women’s work’, the notion of reclamation has always been at the heart of the fight for women’s rights and, indeed, all forms of feminist art. Spanning various centuries quilts, the word ‘quilt’ itself has etymological roots in the thirteenth-century Latin word ‘culcita’ meaning cushion, have proved to provide support for protest groups, movements, and individuals. The use of fabric as a tool for resistance against authoritarian powers has remained a common thread throughout history and continues to be utilised by feminist artists today. From Emmeline Pankhurst to Faith Ringgold, campaigns of consciousness-raising, the history of feminist protest banners is itself a tapestry of female experience - both past and present - a quilt that is continually being added to as the passage of history moves along.

With each new stitch, the narrative only becomes richer.

The art of quilting, and its connection to femininity, has its’ roots in ancient Egypt. Rather than simply a craft, quilting at this time was seen to hold a deep cultural significance within society, with the very fabric being believed to bestow protection and bring good luck to the wearer. Furthermore, the motifs and patterns of the quilts were imbued with symbolism, denoting various spiritual beliefs and values - a notion that would remain true for future forms of protest by feminist groups, as the role of the quilt adapted to ideas of rebellion and subversion. In Europe, quilting became popular during the Middle Ages, with nobles and members of the monarchy commissioning elaborate quilted banners to adorn their palaces. Here, skill and artistry were the most crucial aspects of the craft, whereby these textiles were not simply visual works but rather extensions of the maker, deeply rooted in meaning and social significance.

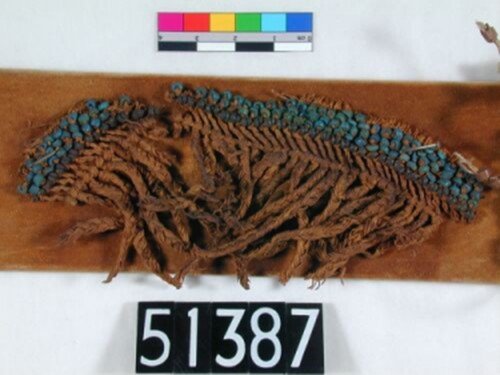

Fragment of looped bed cover found in the ancient Egyptian tomb of Memphis, dated by the excavator Vassalli to c.2500 BC.

Textile fragments found in the Temple of Hathor in ancient Egypt, c.1450 BC.

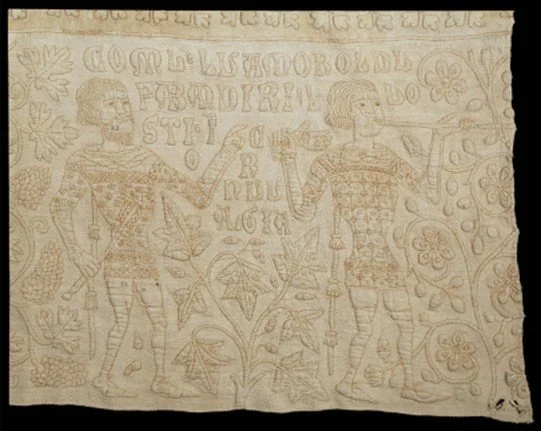

The Tristan Quilt, c.1360-1400, Sicily, Victoria & Albert Museum.

In “Stitched from the Soul” (1990), Gladys-Marie Fry notes that during the early to mid nineteenth century, quilts were used by enslaved African individuals to communicate information about how to escape to freedom via the Underground Railroad - a network of secret routes and safe houses through the United States and into Canada. These quilts would be hung outside one’s home and dictate directions and vital information to those who passed by on their journey to freedom. Art historian Raymond Dobard and Jacqueline Tobin, a college instructor in Colorado, note how much like in ancient Egypt, each and every symbol was charged with such vitality and meaning. A wrench, for example, signified that one should gather up necessary supplies and tools, and a quilt ending with a star, informed the viewer to head north on their journey. Known as ‘freedom quilts’ or ‘quilt codes’, these textiles paved the way for needlecraft to be used as a form of resistance and communication.

Freedom quilt’ made by Sharon Tindall, a contemporary quilter who designs textile works inspired by ‘quilt codes’. Here, Tindall employs a pattern called Flying Geese, in which the triangles and rectangles signify that one should follow the flying geese to Canada and to freedom.

Quilts subsequently took on a feminist role in their engagement with and engendering calls for women’s social and political rights. By the year 1884, feminist protest banners were in abundance, the first recorded instance of their use in the UK, was in 1880 during a suffrage demonstration in Colston Hall in Bristol on the 4th of November. Shortly after, in January 1907, the Artists’ Suffrage League was founded by an array of professional women artists and first chaired by Mary Lowndes. The league was initiated in preparation for the first large-scale public demonstration by the National Union of Suffrage Societies, aiming to “further the cause of Women’s Enfranchisement by the work and professional help of artists … by bringing in an attractive manner before the public eye the long-continued demand for the vote”. Lowndes herself was an accomplished stained-glass and poster artist, designing many of the group’s banners employed during demonstrations such as the Women’s Pageant of Trades and Professions of 1909 at the Albert Hall in Manchester. They gave a visual and aesthetic personality to the marches, allowing the Suffrage Movement to be collectively identified by the key colours of white, green, and purple. Here, banners were not simply placards for information but rather works of art in themselves that encapsulated the gravitas of the cause in their artistry and skill. As Lowndes says herself in her 1909 treatise “On Banners and Banner-Making”, “a banner is a thing to float in the wind, to flicker in the breeze, to flirt its colours for your pleasure, to half show and half conceal a device you long to unravel: you do not want to read it, you want to worship it”.

Thus, instead of mere surfaces upon which words are written, protest banners were and continue to be manifestations of the self, whereby each stitch represents a moment of fighting and a step closer to justice.

Mary Lowndes and her quilted banners during a march for women’s rights in the nineteenth century.

Come the 1970s, and the emergence of the Second-Wave Feminism Movement, quilting was again embraced as a form of both creative and political expression, as well as a reclamation of women’s history. Using quilting as a form of protest served as a way for individuals to connect with the movement’s past, challenge societal norms, and explore themes of identity and empowerment. In addition to the rise of quilting circles, where feminist artists could gather collectively and make reflective pieces that shared their own personal experiences, textile banners were also employed in acts of resistance. They raised awareness on reproductive rights, domestic violence, and gender inequality and were displayed at rallies, marches, and art exhibitions.

A section of the International Honour Quilt, a collective feminist art project initiated in 1980 by Judy Chicago as a companion piece to The Dinner Party. It is a collection of 539 2-foot-long quilted triangles that honour women from around the world.

Feminist artist and quiltmaker Sarah Humphreys, suggests the myth that the origins of quilt making lie entirely in economic necessity. In addition to the making of bedcovers, quilts have historically also been made for gifts, celebration and commemorations, and it is this essence of the personal that, I think, means that quilts lend themselves so well to protest. For, after all, protest in itself, is not a surface-level act, but rather an immersive, raw and visceral experience, filled with emotion and holistically-raised consciousness.