Interviews with artists exhibiting at ArtSpeak: conversations between art and language

Words by Emilia Sogaard, Gill Crawshaw and Laura Nathan

In relation to our upcoming exhibition “ArtSpeak: conversations between art and language”, our head of blog interviewed some of the artists who are exhibiting their work: curator Gill Crawshaw and Laura Nathan, who both use language to explore hidden histories through art.

Gill Crawshaw has curated exhibitions highlighting the very important, yet often forgotten participation of disabled people in UK society. Her first exhibition was “Shoddy” in 2016, and we will be exhibiting a text that was published alongside the exhibition at ArtSpeak. Gill is a disabled person and she used to be involved in the disabled people’s movement. Now she is uses her experience to raise issues around disabled people through curating and to have an activist stance within art institutions.

“Shoddy”, publication cover, 2016.

Her exhibition “Shoddy” includes artworks by a disabled artist and is a play on words. Shoddy can be defined as a type of fabric made from reclaimed or old fabric or scraps; an early version of recycling, invented in West Yorkshire in the 1830’s. Shoddy also describes the UK’s government treatment of disabled people.

Gill Crawshaw: While I was organising this exhibition, I was thinking about the interlinks of textiles and disabled people. The textile industry was the largest in the Industrial Revolution in the UK, and in York it was the main industry right through until the 20th Century, yet we don’t see disabled people reflected in it. I wanted to tell that story of industry and industrialisation, centring people with disabilities.

“Any work that wanted doing” poster, Leeds Industrial Museum, 2023.

By documenting these stories in new publications Gill makes them available to the public, showing the importance of the written language and art to highlight these hidden histories. Currently, at the Leeds Industrial Museum, Gill’s exhibition “Any Work that Wanted Doing”, brings together contemporary disabled artists and the histories of disabled mill workers.

“A Handsome Testimonial”, Gill Crawshaw, 2023.

The other work that we have by Gill in our upcoming exhibition is a zine called “The Handsome Testimonial”, which is about a man who lived in Horbury, Wakefield in the 19th Century. James Scott lived and worked in the Horbury textile mill, and is just one example of a disabled person who was working and contributing to his community, society and the economy. At the core of this zine are the details of his story, which Gill was able to access through the different Censuses. It also takes into account attitudes towards disabled people and education in those times and the hangover of those views now.

Gill curates exhibitions which fight against the pigeon-holing of artists with disabilities. Her exhibitions are of artworks which are multi-layered, complex and well-produced which goes against the preconceived conceptions that many have of the products of disabled artists. Gill highlights the written and verbal stories of disabled people’s lives across the UK and the contemporary disabled artists of today who deserve equal recognition.

“Processing documents 1939-64”, Laura Nathan, 2022.

Laura Nathan is a textile artist who explores her cultural identity, heritage and wellbeing. At ArtSpeak we are lucky to have three of Laura’s artworks. “Processing documents 1939-64” is an extract of what was a 4-metre weave, exploring people’s relatives and family history.

Laura: My family has received loads of documents about my grandparents’ experiences during the holocaust. I had concentration camp documents, letters and Red Cross telegrams. It’s a very overwhelming thing to look at. I printed all of these documents onto the fabric, re-aligned them and photoshopped them in a specific format and size. Then I cut them and wove them into the tapestry. This was my way of dealing with this information, of starting to strip it down and read through it.

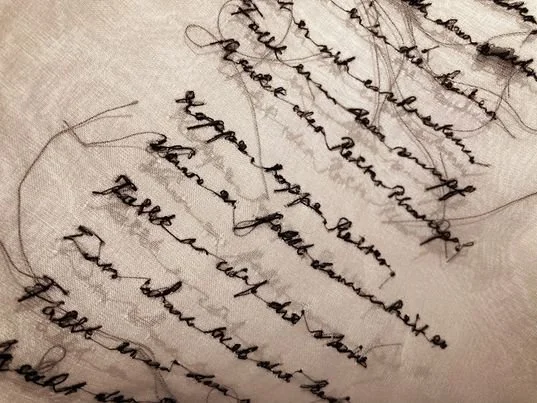

“Hoppe hoppe Reiter”, Laura Nathan, 2023.

Laura: “Hoppe hoppe Reiter” is a German nursery rhyme that my grandma used to sing to us when she sat us on her knee. It was the only time she really spoke German to us, she didn’t want to speak her native language to us because she was so upset by her experiences after she came to England and had lost her family. She was perhaps too traumatised by the sound of the German accent. I have her letter that she got from her parents, beautiful handwritten writing from her mum. The letters in German were a ‘nice memory’ from a very difficult past for her. I wrote out the nursery rhyme, imitating my great grandmother’s handwriting by copying the induvial letters, and then I stitched into fabric. That was my way of connecting to my past and legacy. A lot of my work isn’t about holocaust education, it is more about my relationship with the past and how I learn about it, the anxieties me and my siblings have, and the lack of understanding of our history and needing to understand it. So, a lot of my work could be from anywhere -it is not necessarily to do with the Holocaust – it is a curiosity about the past that I am exploring. My work is about history and obsessively looking at history.

“Fear, Loss, Guilt, Survival”, Laura Nathan, 2023.

The third work we are exhibiting “Fear, Loss, Guilt, Survival”, reflects on how even with fewer documents key emotions such as fear, loss, guilt have been clearly recorded. One letter from the artist’s grandpa repeats phrases like the fear of being separated from his family, the loss of family, his struggle to survive and yet also his guilt for surviving.

Laura: The repetitive process of trying to understand how he’s going on through his life, yet he is constantly burdened with these nightmares. So, the small fabric bundles are me (the artist) trying to keep going with the repetitiveness of this and wrap up the nature of the memory. My work is very literal, it is taking actual words. It is never an abstract reimagining, but it is what has happened. I’m so interested in history, research and documents and so I’m questioning how do we bridge the gap between research and history in a creative way? How do people get the most direct connection to it, how as an artist should I present these documents?

Knowing more German would have helped. Some of the letters are in old German, so Google Translate only helps so much. There is also a difference in accessing the written letters, as my grandma’s dad typed his letters, while her mum handwrote them. This affects the legibility of the words. You can see the thinning out of the letters, as they gradually become shorter, then becoming the telegrams from the Red Cross with 25 words on, as Jews weren’t allowed to send letters anymore.

Both of these artist’s artworks are about history and learning and at ArtSpeak we have curated an exhibition which is about learning and dialogue and the power of language.