Interviews with artists exhibiting at ArtSpeak: “Words became my muse”

Words by Emilia Sogaard

Continuing the theme of ArtSpeak: conversations between art and language, our head of blog interviewed more of the artists exhibiting their work at the Norman Rea Gallery. It was an extremely successful opening night of ArtSpeak on the 4th of October and it was so special to witness the engagement of the public with the artworks and some of the artists themselves. One of the artworks exhibited at the Norman Rea Gallery was “Can You See Me?” by blind, braille artist Clarke Reynolds.

Seeing without Seeing, Clarke Reynolds logo.

Clarke uses the tagline ‘Seeing without Seeing’ for his artistic practice. When interviewing him it was clear how his artwork is derived entirely from his experiences, and this emotion is transmitted into the work and its ability to engage a viewer.

Clarke: What is really important is the nature of how I stumbled across art. Growing up in a council flat area in Portsmouth my school took me to an art gallery called Aspex, when I was 6 years old and blind in one eye. I knew then, going into that building, I was going to be an artist. I never gave up on that dream. In terms of my art, I stumbled across braille. My friend gave me a Perkins typewriter. It has six keys as Braille is made out of 6 dots. It’s almost like playing chords on a musical instrument. Braille is mathematical, for example: A is 1, B is 1 and 2, C is 1 and 4. I learnt braille in 3 weeks just because I didn’t see it as a letter, I saw it as a pattern. My Rosetta Stone was a big artwork on this, which has the braille alphabet. It went off to Rome a couple of years ago for Rome Art Week. The concept of the work was very clear – it was like a eureka moment, just as a typographer uses a letter, why don’t I use a dot?

Clarke: When you are visually impaired, words are so important to describe. Words became my muse. My conversation, the stories of my life became embedded in my artwork.

Clarke Reynold’s colour coded braille alphabet.

How do you see colours?

Clarke: I don’t see with my eyes; we see with our brains and with the information that’s stored in it. I know what colours look like and I have a memory of colour. I don’t see colours as I remember them, so what I am doing now is creating new memories of how I perceive colour through the tonal differences, instead of what is physically there. The colours aren’t random, I look at the combination of letters appearing in words and then I use Colour Theory. Just as a painter paints a portrait or a landscape I’m painting in words, it is the same application. ‘E’ is orange, ‘R’ is blue – a lot of words end in ‘er’, and so the use of complementary colours. With 26 colours not one colour dominates in my decoded braille alphabet, they all marry together.

Clarke: I’m a braille typographer. Braille should be everywhere – it should be universal. It should be made law for example, that all toilets have braille letters (Male, Female, Unisex) on in accessible places. I am pushing the boundaries and moving braille forward into the 21st Century. Smart braille should be like smart lettering. Smart lettering is everywhere, why can’t braille be like that?

Clarke Reynolds at Aspex Gallery, first contemporary art exhibition, 2022.

When talking about the spaces and institutions Clarke exhibits at, his response was very interesting and important to recognise. He also commented that as a blind person, galleries don’t like him. Audio description is often boring, offering a formal visual analysis in a monotonous voice, with no relation to what you see. Audio description should include the emotional response, allowing different intonations of the voice.

Clarke: It is an important question to talk about. I was an artist before I lost my sight and in society major galleries and NGOs view someone with a disability as doing art as a hobby. It is really important that my art is now seen in the public. I want my art to be engaged with. If I can open doors, push barriers, then in the future visually impaired children growing up will see that they can be artists too – there are no limitations.

“Can You See Me?”, Clarke Reynolds, this piece at the Norman Rea Gallery was one of the first pieces Clarke did in braille.

Clarke: I wanted people to see me as an artist not just a hobbyist. So, on a large canvas fabric, in high-vis braille it spells out ‘Can you see me?’. The connotations of the visibility of high-vis are also at play here. When they are displayed this is displayed as a giant ‘ME’ in braille. It is this playfulness of words.

Clarke gets a lot of inspiration on public transport, as when he’s walking his concentration is on finding his way, not getting run over. But on the bus or the train is where many of his ideas come from. Speaking to amalgam artist John Sherwood in the Norman Rea Gallery it was interesting to hear that he too was inspired by conversations he overheard on public transport. John spoke about how illustration, conceptional or instinctive, is all language.

John: In a way to call art a language, is a truism. It’s obvious. The verbal language and the visual language do overlap and interact.

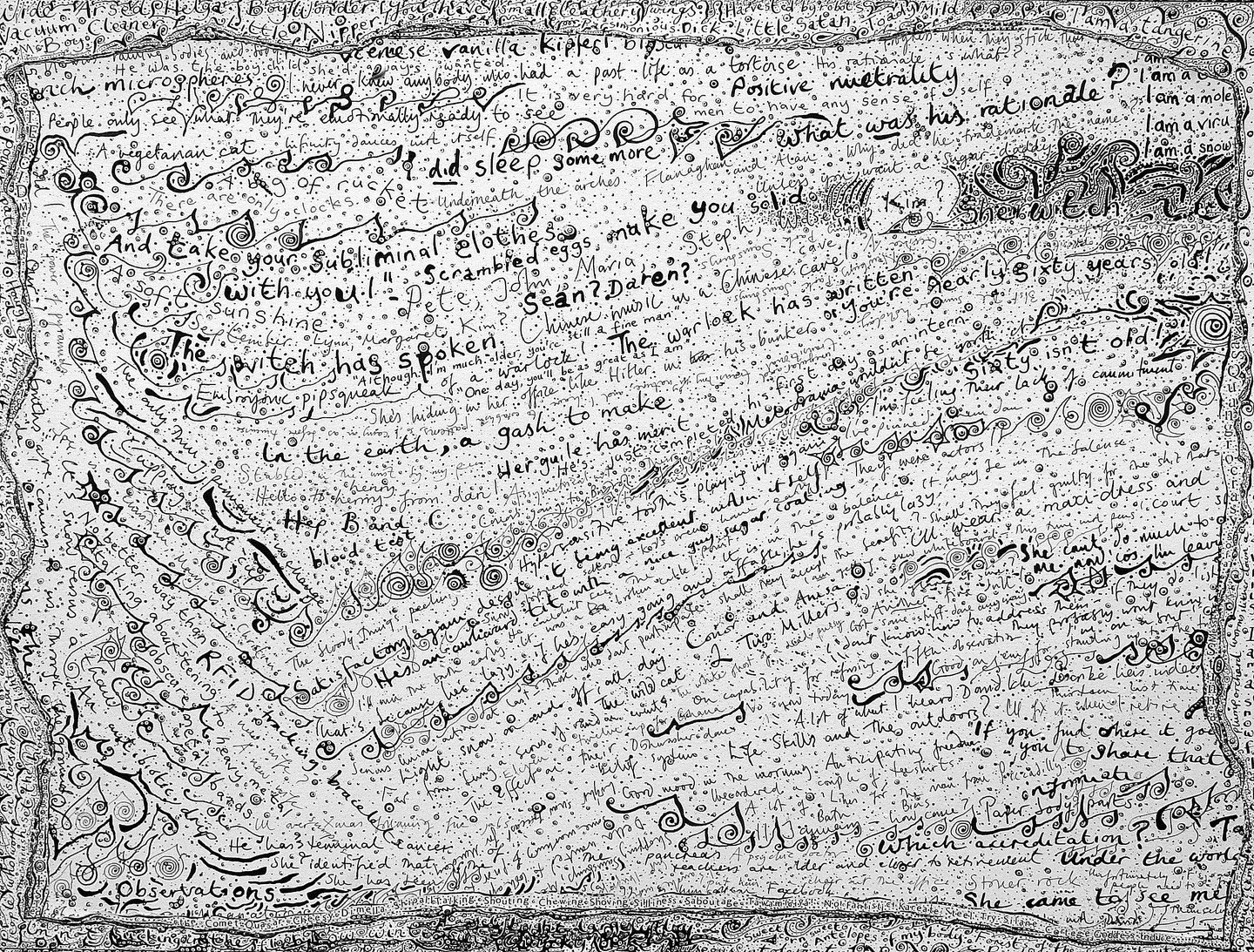

“Black Writing”, John Sherwood, 2023.

Speaking about the work he exhibited, John said it is a mixture of random thoughts, towards the time when he retired.

John: There are vague references to people that I was working with, some of it put in poetic language. The words can be anything, literally anything. A lot of the words in this were me talking about people I knew. There are other things as well, some of it are drole references, things I pick up on the street. Something that strikes me as odd, uncanny, strange – especially taken out of context, surreal. I’m interested in art as language. A line could become a word, the words themselves can be poetic or factual, the lines themselves take on a feeling. A lot of the things in this picture, the content, is sort of magical. The lines are spontaneous, but you get a sort of vocabulary of the shapes you use, you still get a habit.

ArtSpeak is open until the 20th October, visit the gallery to explore your connection to language and interpret how art speaks to you.